Mastering Decision Making and Problem Solving: Part 1 - Strategies for Success

Being in an organization's management and leadership position requires making many decisions. Depending on how many decisions one has to make in a short period, this can result in decision fatigue. According to registered psychotherapist Natacha Duke, MA, RP, decision fatigue is a phenomenon where the more decisions a person makes over a day, the more physically, mentally, and emotionally depleted they become. If this kind of depletion continues, an individual can experience job burnout, and if not dealt with quickly, it can result in a complete lack of interest in their job and other aspects of their life.

One way to manage decision fatigue and possibly burnout is to reduce the stress of making decisions and the number of decisions made through delegation and distributed leadership.

However, the biggest challenge I see leaders and managers have with delegation is a fear of the quality of the decisions made.

In this article, I’ll outline how to identify decisions to be delegated and what tools or frameworks can be used to help make those decisions. I’ll also discuss decision-making pitfalls to avoid.

Structured Approaches to Making Complex Decisions

Types of Decisions To Delegate

Embracing a distributed leadership mindset means delegating the authority to make decisions to those closest to the work. A few things are required before this can be done successfully.

The first is ensuring that the organization is competent to make these decisions. By that, I mean if there’s a specific business domain, it’s well understood, so people understand the context in which the decisions are being made. From a technical standpoint, they have the required knowledge and skills to make informed decisions.

The second is ensuring well-defined boundaries. I typically refer to these boundaries as guard rails that provide freedom within the organization.

Clearly defined processes, a focus on outcomes—not output—building a culture of continuous improvement, and fostering a culture of risk-taking allow the following types of decisions to be made organizational-wide and do not require a decision-making bottleneck.

- Simple decisions: are straightforward choices that don't require extensive analysis or consideration. Examples include choosing what to wear or what to have for lunch.

- Routine decisions: are decisions made frequently and follow a well-established process or set of rules. Examples include reordering supplies or approving standard expense reports.

- Operational decisions: are decisions related to an organization’s day-to-day functioning, such as scheduling, resource allocation, and quality control.

- Tactical decisions: are decisions that support the implementation of ****an organization's strategic objectives. Examples include choosing marketing campaigns, hiring new staff, or selecting vendors.

- Group decisions: are decisions made by a team or group of people that require collaboration, communication, and consensus-building.

- Data-driven decisions: are based on quantitative or qualitative data analysis using statistical analysis, machine learning, or data visualization tools.

- Crisis decisions: are decisions that must be made quickly in response to an unexpected event or emergency. Examples include dealing with a natural disaster, a product recall, or a data breach.

Another filter to apply is what Jeff Bezos calls Type 1 and Type 2 problems. The question to ask is, is this decision reversible? If it is reversible, it’s a Type 2 problem, and it’s “safe” to decide and act quickly and probably delegate. If it’s not reversible, then it’s a Type 1 problem, and this decision should be made slowly before acting and shouldn’t be delegated.

Here’s a snippet from Jeff Bezos’s letter to shareholders in 1997:

As organizations get larger, there seems to be a tendency to use the heavy-weight Type 1 decision-making process on most decisions, including many Type 2 decisions. This results in slowness, unthoughtful risk aversion, failure to experiment sufficiently, and consequently diminished invention.

I have seen this happen in companies with only 20-30 people. Size isn’t necessarily a requirement for this problem to occur. The real issue I see is that as companies get larger, the CEOs and executives become dumber, in the sense that an increasing number of things are happening that make it difficult for them to be aware of and have direct involvement with. This can be particularly jarring for founders who have, up to that point, been very involved in every aspect of the business.

Types of Decisions Not to Delegate

These decisions should be made slowly and thoughtfully, not alone, and typically fall into the domain of complex and Type 1 decisions. Typically, the organization leadership team would make these decisions together, as they require a broad breadth of expertise and experience.

- Strategic decisions: are high-level decisions that shape an organization’s direction and long-term goals. Examples include entering new markets, developing new products, or merging with another company.

- Ethical decisions involve moral or ethical considerations, such as determining the right course of action in a situation where different values or principles conflict.

Complex decisions

Complex decisions involve multiple factors, stakeholders, and potential outcomes, making them more challenging and time-consuming than simple or routine decisions. Some characteristics of complex choices include:

- Multiple variables: Complex decisions involve considering numerous interconnected variables influencing the outcome, such as financial, social, environmental, and political factors.

- Uncertainty: The outcomes of complex decisions are often uncertain, as the decision-maker may not have access to all relevant information or be able to predict how different factors will interact.

- High stakes: Complex decisions often have significant consequences for individuals, organizations, or society as a whole, which can make the decision-making process more stressful and challenging.

- Conflicting objectives: Stakeholders may have competing interests or priorities, making it difficult to find a solution that satisfies all parties involved.

- Long-term impact: The effects of complex decisions often extend far into the future, requiring decision-makers to consider short-term and long-term consequences.

- Ambiguity: Complex decisions may involve unclear or incomplete information, requiring decision-makers to use their judgment and expertise to fill in the gaps.

Examples of complex decisions include developing a corporate strategy, designing public policies, or making medical treatment choices for patients with multiple health conditions.

To effectively tackle complex decisions, decision-makers often rely on structured approaches, such as decision-making frameworks, to break down the problem into more manageable components and systematically evaluate potential solutions.

Importance of structured approaches

Structured approaches to decision-making are crucial when dealing with complex decisions because they provide a systematic and organized method for navigating the intricacies of the decision-making process. Here are some key reasons why structured approaches are essential:

- Clarity and focus: Structured approaches help decision-makers define the problem or opportunity, ensuring all stakeholders understand the issue. This clarity helps maintain focus throughout the decision-making process, preventing the team from getting sidetracked by peripheral concerns.

- Comprehensive analysis: By following a structured approach, decision-makers are more likely to thoroughly analyze the situation, considering all relevant factors and potential outcomes. This thorough analysis reduces the risk of overlooking critical information or unintended consequences.

- Objectivity: Structured approaches help minimize the influence of cognitive biases and emotional reactions by providing a framework for objective evaluation. By following a predefined process, decision-makers base their choices on evidence and logical reasoning rather than gut instincts or personal preferences.

- Improved communication: Structured approaches provide a common language and framework for discussing the decision-making process, facilitating better stakeholder communication. This improved communication can lead to greater buy-in and support for the final decision.

- Enhanced transparency: Structured approaches increase transparency and accountability by documenting the steps and rationale behind each decision. This transparency can be critical when external parties scrutinize decisions or when the decision-making process needs to be audited.

- Increased efficiency: While it may seem counterintuitive, investing time in a structured approach can make the decision-making process more efficient in the long run. By frontloading the work of defining the problem, gathering information, and establishing evaluation criteria, decision-makers can avoid unnecessary delays and dead ends later in the process.

- Better outcomes: Ultimately, the goal of using structured approaches is to make better decisions. By carefully considering all aspects of the situation and systematically evaluating potential solutions, decision-makers are likelier to choose a course of action that leads to positive outcomes for all stakeholders involved.

Structured approaches to decision-making are essential for navigating complex decisions because they provide a roadmap for analyzing the situation, evaluating options, and reaching a well-reasoned conclusion. By embracing these approaches, organizations and individuals can improve the quality and effectiveness of their decision-making, even in the face of uncertainty and complexity.

Decision-making frameworks

SWOT Analysis

SWOT stands for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. It is a strategic planning tool used to evaluate the internal and external factors that can impact an organization's or individual's success.

Components:

- Strengths: Internal attributes that give an advantage (e.g., skilled workforce, strong brand reputation)

- Weaknesses: Internal attributes that put one at a disadvantage (e.g., outdated technology, limited financial resources)

- Opportunities: External factors that could be exploited for benefit (e.g., emerging markets, new technologies)

- Threats: External factors that could cause problems (e.g., increased competition, economic downturn)

Example: A company considering launching a new product might use a SWOT analysis to assess its internal capabilities and the external market conditions before deciding.

Decision Matrix

A decision matrix is a tool for evaluating and prioritizing different options based on weighted criteria.

Components:

- Options: The potential choices or solutions to the problem

- Criteria: The factors that will be used to evaluate each option (e.g., cost, feasibility, impact)

- Weights: The relative importance assigned to each criterion

- Scores: The performance of each option against each criteria

Steps:

- Identify options and criteria.

- Assign weights to criteria.

- Score each option against each criterion.

- Calculate weighted scores and total scores for each option.

- Select the option with the highest total score.

Example: A company trying to decide which software vendor to choose might use a decision matrix to evaluate each vendor based on criteria such as price, features, user-friendliness, and customer support.

PEST Analysis

PEST stands for Political, Economic, Social, and Technological. It is a framework used to analyze the macro-environmental factors that impact an organization's performance.

Components:

- Political factors: Government policies, regulations, and political stability (e.g., tax policies, trade agreements)

- Economic factors: Economic growth, interest rates, inflation, and exchange rates (e.g., GDP growth, consumer spending)

- Social factors: Demographic trends, cultural norms, and consumer behavior (e.g., aging population, health consciousness)

- Technological factors: Technological advancements, innovations, and disruptions (e.g., artificial intelligence, mobile technologies)

Example: A company planning to expand into a new country might use a PEST analysis to assess the viability and potential challenges of entering that market based on the political, economic, social, and technological conditions.

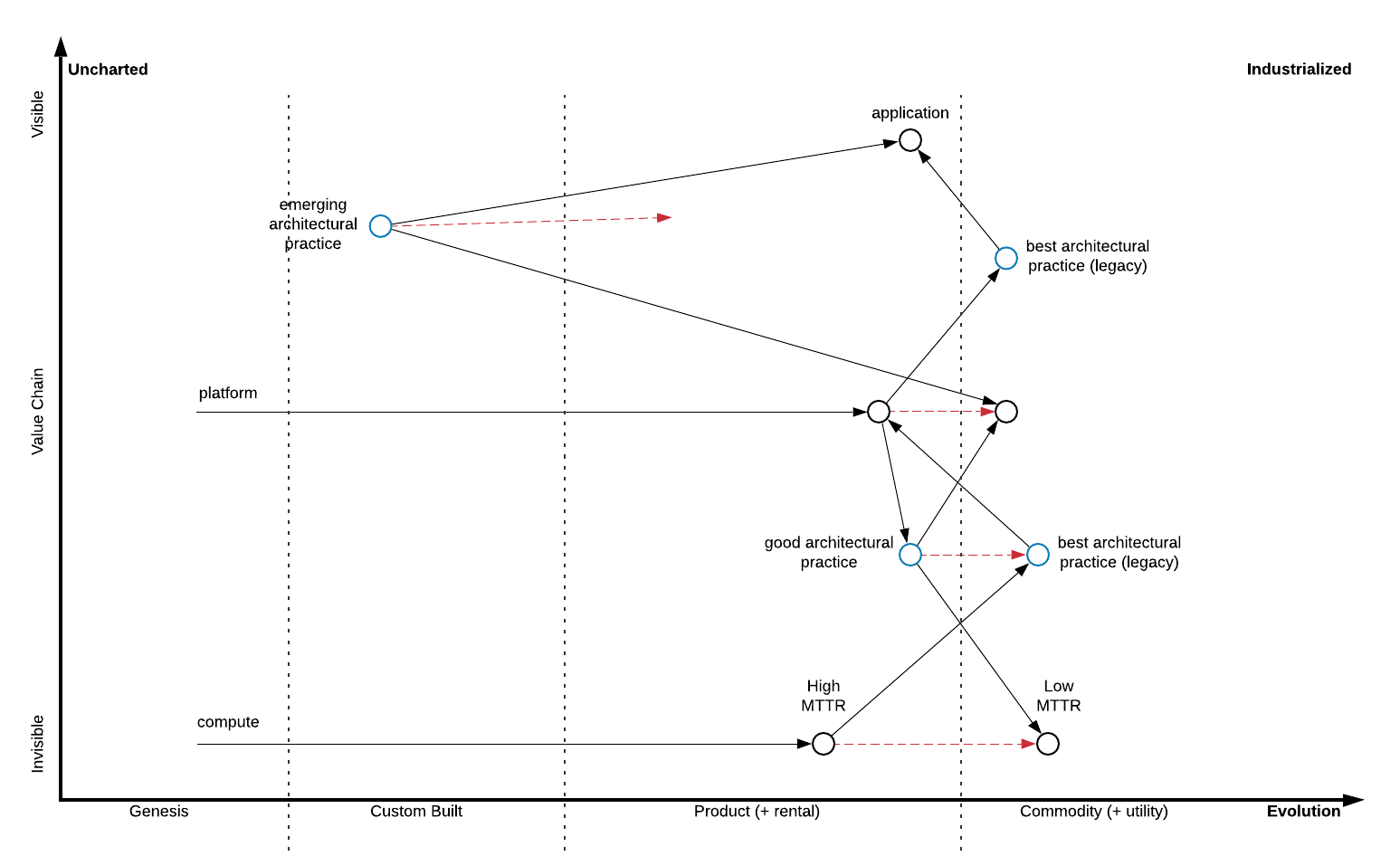

Wardley Maps

Wardley Maps is a strategic planning tool that helps visualize the landscape of a business, market, or ecosystem. Developed by Simon Wardley, the maps help organizations make better decisions by understanding the relationships between different components and their evolution over time.

Wardley Maps offer a robust framework for understanding the complex interactions between different components in a business or market. By mapping out the value chain, assessing the evolution of each element, and analyzing the resulting landscape, organizations can make more informed decisions about where to invest, what to outsource, and how to position themselves for long-term success.

Components

- Value Chain: A company performs activities to deliver a valuable product or service to the market.

- Evolution: The progression of a component from its earliest stage (genesis) to its most advanced stage (commodity).

- Visibility: The extent to which a component is visible to the user or customer.

- Anchor: The user needs that the value chain aims to satisfy.

Stages of Evolution

- Genesis: The earliest stage of a component, characterized by high uncertainty and low standardization (e.g., custom-built solutions).

- Custom Built: Components are tailored to specific needs but require significant effort and expertise to create and maintain.

- Product: The component becomes more standardized and can be sold as a product to a broader market (e.g., commercial off-the-shelf software).

- Commodity: The component is highly standardized, widely available, and easily interchangeable (e.g., cloud computing services).

Steps to Create a Wardley Map

- Identify the anchor (user need)

- Map out the value chain.

- Assess the visibility of each component.

- Determine the stage of evolution for each component.

- Analyze the map to identify opportunities, risks, and strategic choices.

Examples

Online Retailer:

- Anchor: Customers need to purchase products online

- Value Chain: Website, payment processing, inventory management, shipping, customer service

- Evolution: Website (product), payment processing (commodity), inventory management (custom built), shipping (product), customer service (custom built)

Ride-sharing App:

- Anchor: Customers' need for convenient transportation

- Value Chain: Mobile app, mapping and navigation, payment processing, driver management, customer support

- Evolution: Mobile app (product), mapping and navigation (commodity), payment processing (commodity), driver management (custom built), customer support (product)

Visualization:

Benefits of Wardley Maps

- Provides a visual representation of the competitive landscape.

- It helps identify areas for innovation and differentiation.

- Facilitates communication and alignment among stakeholders.

- Enables better strategic decision-making based on the evolution of components.

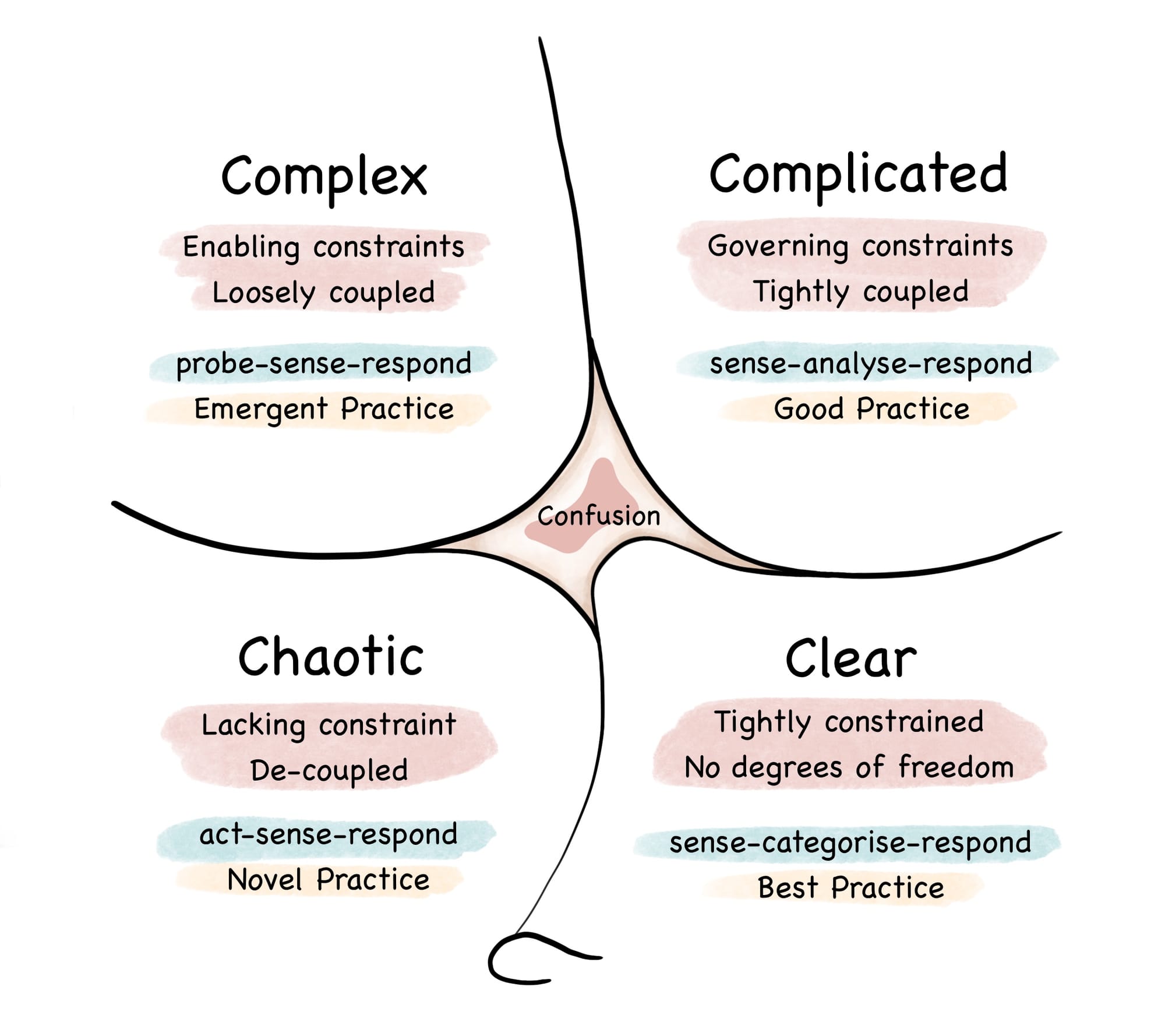

Cynefin Framework

The Cynefin framework is a decision-making tool that helps leaders and managers understand the complexity of different situations to make better decisions. Developed by Dave Snowden in 1999, it categorizes issues into five distinct domains, each requiring a different approach to problem-solving and decision-making.

The Five Domains of Cynefin:

Clear (formerly Simple or Obvious) Characteristics: Problems in this domain have clear cause-and-effect relationships that are easily understandable by everyone. Best practices are known and widely accepted.

Decision-Making Approach: Sense – Categorize – Respond

- Sense: Identify the situation.

- Categorize: Match it to known patterns.

- Respond: Apply best practices.

Example: Following a standard operating procedure for routine tasks.

Complicated Characteristics: Problems in this domain have clear cause-and-effect relationships but are not immediately apparent and require expert analysis. There are multiple correct answers.

Decision-Making Approach: Sense – Analyze – Respond

- Sense: Gather data.

- Analyze: Use expert knowledge to understand the situation.

- Respond: Implement good practices.

Example: Diagnosing issues in machinery that require specialized engineering knowledge.

Complex Characteristics: Problems in this domain have unknown cause-and-effect relationships that can only be understood retrospectively. The system is dynamic and unpredictable.

Decision-Making Approach: Probe – Sense – Respond

- Probe: Conduct safe-to-fail experiments.

- Sense: Observe the results.

- Respond: Amplify successful actions and dampen failures.

Example: Developing a new market strategy with uncertain customer preferences and competitor actions.

Chaotic Characteristics: Problems in this domain have no apparent cause-and-effect relationships and require urgent action. The environment is highly turbulent.

Decision-Making Approach: Act – Sense – Respond

- Act: Take immediate action to stabilize the situation.

- Sense: Assess the impact of the action.

- Respond: Adjust as necessary to gain control.

Example: Crisis management during a natural disaster.

Aporetic (formerly Disorder) Characteristics: This is the state of not knowing which domain a situation belongs to. Decisions are often based on personal preferences rather than situational appropriateness.

Decision-Making Approach: Break down the situation to categorize it into one of the other domains.

Example: There is confusion and lack of clarity about how to proceed.

Examples:

Complicated Domain Example:

Scenario: An automobile manufacturing company faces a technical issue with a new engine design.

Decision-Making Approach: Sense – Analyze – Respond

- Sense: Gather detailed data about the engine's performance.

- Analyze: Bring in mechanical engineers to diagnose the problem using their expertise.

- Respond: Implement the recommended engineering solutions.

Outcome: The expert analysis leads to a fix that resolves the engine issue and improves the design for future production.

Complex Domain Example

Scenario: A tech startup is trying to develop a new app that caters to evolving user preferences in social media.

Decision-Making Approach: Probe – Sense – Respond

- Probe: Launch small-scale beta tests of different app features.

- Sense: Collect and analyze user feedback and engagement data.

- Respond: Enhance and expand successful features while discarding or modifying poorly performing ones.

Outcome: The iterative process allows the startup to refine the app in response to natural user behavior, leading to a more successful product launch.

Visualization

Benefits:

- Enhanced Decision-Making: The framework helps leaders and managers identify a problem’s nature and choose the most appropriate decision-making approach, ensuring more effective and contextually suitable solutions.

- Improved Resource Allocation: By categorizing problems into different domains, organizations can allocate resources more efficiently, focusing expert analysis on complicated issues and quick actions in chaotic situations.

- Adaptive Strategies: The Cynefin Framework promotes adaptive and flexible strategies, especially for complex and unpredictable environments, by encouraging safe-to-fail experiments and iterative learning.

- Risk Management helps identify and manage risks by preventing the application of inappropriate solutions (e.g., avoiding simple solutions for complex problems), thereby reducing the likelihood of failure and unintended consequences.

Conclusion

These frameworks provide structured approaches to decision-making by helping organizations and individuals systematically analyze the factors that can influence the success or failure of a particular course of action. These tools allow decision-makers to make more informed and strategic choices aligned with their goals and objectives.

Steps in structured decision-making

- Identify the problem or opportunity.

- Gather relevant information

- Generate alternatives

- Evaluate and select the best alternative.

- Implement and monitor the decision.

Mastering decision-making and problem-solving is crucial for success in leadership and management roles. Decision fatigue can be challenging, but delegation and distributed leadership strategies can help alleviate this burden. When delegating decisions, it's essential to consider the organization’s competency, clearly define boundaries, and differentiate between simple, routine, operational, tactical, group, data-driven, and crisis decisions.

Strategic and ethical decisions should not be delegated and require careful consideration by the leadership team. Structured decision-making approaches are essential for complex decisions involving multiple variables, uncertainty, high stakes, and long-term impact. Frameworks like SWOT analysis, decision matrices, PEST analysis, Wardley Maps, and the Cynefin Framework provide systematic methods to analyze the situation, evaluate options, and reach well-reasoned conclusions.

By embracing these strategies and tools and following a structured process of problem identification, information gathering, alternative generation, evaluation and selection, and implementation and monitoring, leaders can enhance the quality and effectiveness of their decision-making. Investing the time upfront to employ a thorough, objective approach pays dividends in better outcomes, even in the face of complexity and uncertainty. Mastering the art and science of decision-making is an ongoing journey well worth the effort for any leader striving for success.